A Broad Background for Genesis 1-12 and Our Six Studies

Scholars now believe much of Genesis 1 was written by a priest for the people of Jerusalem and Judah who had been taken in slavery to Babylon around the year 587 BCE (Before the Common Era). In addition, these scholars also believe that it was this priest who took the stories that we find in Genesis 2-12 and edited them in the way that we encounter them now in the Christian Bible. The Hebrew people had lost everything – their homes, family members, Temple, government, land, economy. They’d lost their freedom and were now enslaved in a foreign land. And they wondered, had they lost their God? Had God abandoned them?

This anonymous priest was not writing history and science lessons for the exiles. Rather he (for there were no women priests at that time) was giving them hope and encouragement. He was giving them a map that they could use to find their way through this devastating and difficult experience. And while our experience of COVID is nothing like what those long-ago exiles went through, only the very oldest people alive today have any memory of the last time our world went through something like COVID.

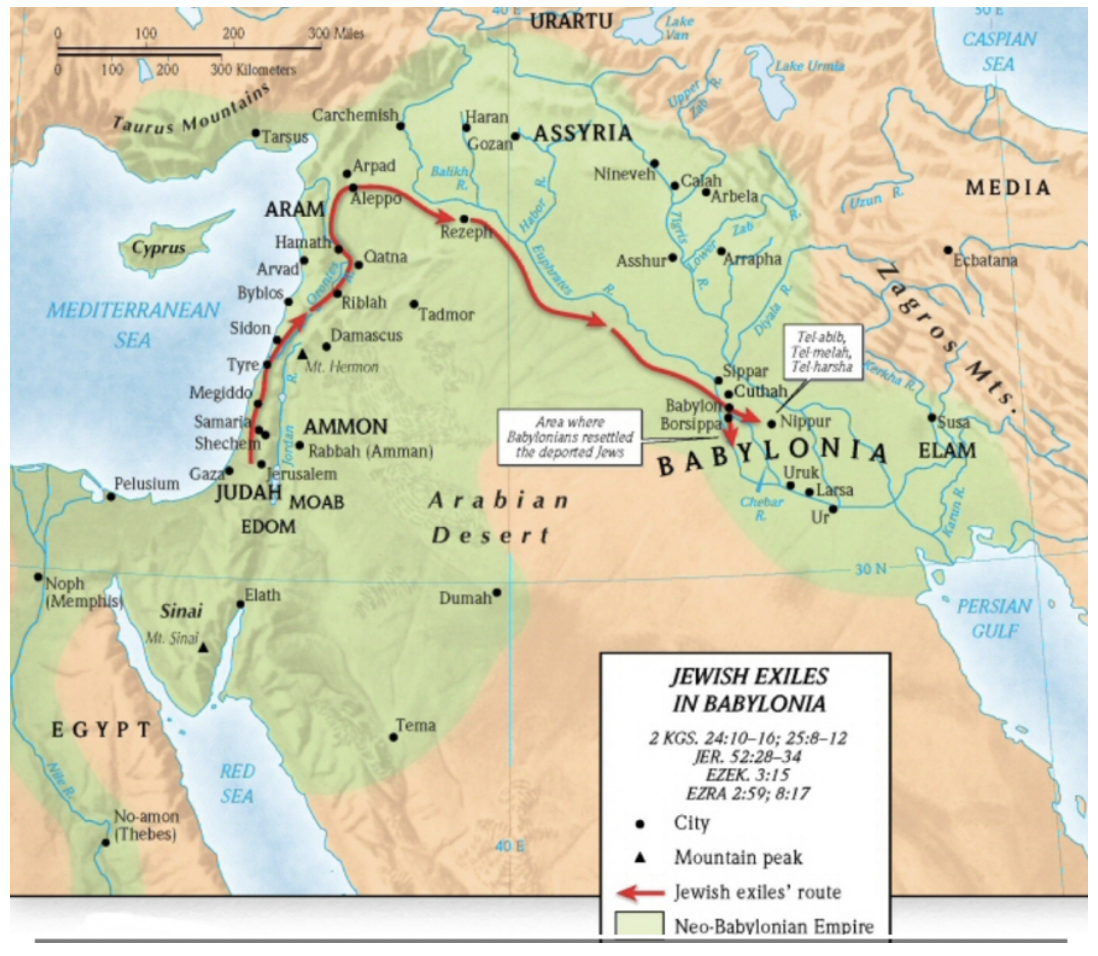

So the priest’s motivation? The priest wrote Genesis 1 as a statement of God’s love for and presence with the exiles. The priest then edited stories that that were part of the ancient oral history of the Hebrew people (Genesis 2-11), linking those ancient stories directly to what the exiles had experienced. In this section, he was crafting a story of what went wrong. The priest was writing to a group of people who has been forced out of their homeland – just like Adam and Eve had been forced out of the Garden of Eden. He wrote about the Great Flood, which they knew experientially as the exile. He wrote about faithful Noah – a model for exiles longing to follow God into an unknown new future. He wrote about the Tower of Babel. The tower was like the ziggurats the exiles walked by every day—monuments to the hubris of mighty Babylon the Great—the empire that destroyed their Temple, killed their families, stole their money and took them on an 800 mile forced march from Jerusalem to slavery in Mesopotamia (see map on page 2).

Then as we move from Genesis 11 to Genesis 12, we will see the staggering contrast between the power of Babylon and the power of God. Immediately after this chapter about the hubris of empire, God forms a covenant with one elderly couple, Abraham and Sarah. They have no children. Sarah is beyond the age of child bearing. In the eyes of the world, they had as much promise for changing the world as elderly people in nursing homes in the age of COVID-19. But God promises to make them the parents of a people who one day will be as numerous as the stars in the sky and the grains of sand on the shore of the seas. Abraham and Sarah are nomads who own no land. But God promises to give them land that extends from the Nile to the Euphrates (Genesis 15:18). And not only that, God promises that through Abraham and Sarah, “all the families of the earth shall be blessed” (Genesis 12:3.). The priest author wants the exiles to know that God has chosen them and has loved them for a very long time: back to Abraham and Sarah, back to the act of creation itself. But he also wants them to know that God’s love and blessing goes beyond them to encompass all people and all of God’s non-human creation.

So, let’s join together and see what this priest from long-ago and these ancient texts can say to us as we make our way together as God’s children living in God’s world living in this time of global pandemic.

Genesis 1 Background

Genesis 1 is, obviously, the Bible’s first story. And, as we all know, it is a story about creation. But it wasn’t put at the beginning simply because it’s a story about creation. There are other wonderful stories of creation in the Bible. Each is different. The differences reflect the historical circumstances of each writing. We find the other creation stories in Job 38-41, Psalm 104, Psalm 74:12-17, Proverbs 8:22-31, Ecclesiastes 1:2-11; 12:1-7, and excerpts in Isaiah 40-55.

So why is this particular seven-day creation story placed at the beginning of the Bible? Genesis 1 was written in the sixth century BCE. Most of these other biblical creation stories were already well known. Why not use one of them? Clearly, whoever edited the Pentateuch, the first five books of the Old Testament, put this creation story at the beginning of the Bible because he saw its enormous significance for the entire Bible.

So what makes this particular creation story so significant? To understand why this story is so significant, we first need to come to know different aspects of its historical context. Specifically, we’ll look in more detail at the exile, the priest author of Genesis, and the literary characteristics of Ancient Near East creation stories.

Historical Context: The Exile

When we study the Bible, it’s always helpful to have an understanding of what’s happening historically when the story was written. As a reminder from the introduction, most scholars today agree that Genesis 1 was written in the sixth century BCE when the Hebrew people were exiles in Babylon. The exile was one of the most devastating times in the history of the Hebrew people.

What events precipitated the exile? The armies of Babylon invaded Jerusalem in 597 BC, 587 BC and again in 582 BC. They demolished the city and the temple. They killed men, women and children. In three deportations, they exiled thousands of Jews, Israel’s middle and upper class, to Babylon some 800 miles from Judea. The poor they left to farm the land for Babylon. They terminated the two institutions that had formed the center of Israel’s life for centuries: the Temple and the Davidic kingship. The Bible describes the destruction of Jerusalem in 2 Kings 24-25.

In several places in the Old Testament, we read about what this devastation was like for the Hebrew people. Here’s an example of their experience as described in Lamentations,

3Judah has gone into exile with suffering

and hard servitude;

she lives now among the nations,

and finds no resting place;

her pursuers have all overtaken her

in the midst of her distress.

4The roads to Zion mourn,

for no one comes to the festivals;

all her gates are desolate,

her priests groan;

her young girls grieve,

and her lot is bitter.

5Her foes have become the masters,

her enemies prosper. -Lamentations 1:3,4,5a

Here’s another example from a Psalm:

1By the rivers of Babylon—

there we sat down and there we wept

when we remembered Zion.

2On the willows there

we hung up our harps.

3For there our captors

asked us for songs, and our tormentors asked for mirth,

saying,

“Sing us one of the songs of Zion!”

4How could we sing the Lord’s song in a foreign land?

-Psalm 137:1-41

As we read through Genesis 1 to 12 and especially in our first session on Genesis 1, let’s be asking ourselves, what is the author saying to these exiles? How is he connecting with them? What’s on the map he is giving them?

Historical Context: Authorship of the Genesis 1

Who wrote Genesis 1? What was he teaching these people whose lives had become, in the graphic words of Genesis 1:2, a “formless void” covered by darkness?

Today most scholars today think that Genesis 1 was written by a priest—part of what’s known as “P” or priestly source of the Old Testament. And most scholars, like Ronald Hendel, Professor of Hebrew Bible and Jewish Studies at the University of California, Berkley, believe the priest who wrote Genesis 1 also edited Genesis 2 to 11 in the sixth century BCE during the exile in Babylon. Hendel writes, “The Creation account in Genesis 1:1-2:3 was written by P, an Israelite priest, around the sixth century BCE.”[2]

Mark S. Smith, Professor of Old Testament at Princeton Theological Seminary, observes that this author priest was writing at the same time as Ezekiel (also in exile in Babylon), Isaiah chapters 40-55 (author unknown) and Jeremiah (who remained in Judah until he was captured and taken to Egypt). All of these amazing writings in the Hebrew Bible emerge at that time when Israel is attempting to deal with the worst disaster in its history. He writes, “These great biblical works all contain important texts that probe the nature of God’s power and the reality of God for Israel in a time dominated by foreign powers… These major biblical works were engaged in a conversation over the nature of God and the world during this period of Israel’s deepest crisis.”[3]

Who were the priests of Israel? What did they do? In his book, The Priestly Vision of Genesis 1, Mark Smith describes the role of priests as writers and worship leaders at the Temple in Jerusalem. He writes,

To imagine the priestly context, we may think in terms of a priestly tradition at work for hundreds of years, beginning as early as the eighth century BCE.… This priesthood maintained the routine of sacrifices and the cultic calendar at the Jerusalem Temple, and it was responsible for producing texts that helped to serve these priestly functions. In their situation, priestly writers worked with texts accessible to them through several written traditions as well as various oral channels.[4]

Of course, by the time this priest was writing Genesis 1, the Temple has been destroyed by Babylon. It was a time of destruction, displacement and uncertainty. In his writing, we see a powerful statement of hope and direction. As we work our way through Genesis 1, we will see the priest’s passion for God, God’s people and all creation. In this time of coronavirus, the priest’s passion is a great gift to us. It is a map that will guide us as we travel through this uncertain time.

Historical Context: Genesis 1 as Ancient Literature

In the past 30 to 40 years, our knowledge of the Ancient Near East (known to scholars as ANE) has multiplied. We now know that all ancient near eastern cultures (specifically Akkadian, Sumerian, Egyptian, and Ugaritic cultures) had creation stories. Scholars know the specific ways in which they are similar and the ways they are distinct from one another.

The Hebrew people lived on a narrow land bridge between these cultures. These cultures were linked together by trade routes that extended from Egypt to Europe to the Silk Road and China. And they were linked by countless wars. These ANE cultures knew each other. So it’s not surprising that in Genesis 1, we see several characteristics from the creation stories of these surrounding cultures. John H. Walton has written an entire book on the influence of these stories on Genesis 1.[5]

Each week we’ll see a few of these important influences. We’ll look at two today. I think you’ll find them interesting and perhaps surprising.

Influence #1 – In Ancient Stories of Creation, Is the Focus Material or Functional

We live in a scientific world. Our orientation is material. We want to know how material things came into existence. For example, all of us know about the big bang—how stuff came into being, and about evolution—how stuff evolved. But in the ancient world, the pre-scientific world, people were much more interested in how something functioned, rather than what it was made from. In culture after culture, creation stories are concerned with the function of what exists—the role it has in the cosmos.

People alive today often try to ask material questions of these functional creation stories. But that’s a little like looking for chicken eggs in a fabric store. Living in a scientific world, we are understandably curious about material origins. But that’s not what ancient creation stories are interested in. As you read Genesis 1, notice the many times function is described. In other words, notice what the different parts of creation were created to do.

Influence #2 – The Difference Between Nonexistence and Existence

In our 21st century material orientation, we tend to assume that if something is not material, it doesn’t exist. But the ancients, with their functional orientation, assumed that if something has no function, it doesn’t exist. In his book, Conceptions of God in Ancient Egypt: The One and the Many, Eric Hornung observes that in ancient Egypt, “that which is nameless does not exist.”[6] In the ancient world, name identifies function. So if there’s no name, i.e. no known function, it doesn’t exist.

Virtually all ANE creation stories begin with a primeval world. The primeval world isn’t empty, it’s got “stuff” in it. But the stuff has no knowable function. The primeval world often contains forces symbolized by chaotic unbounded waters, symbolic darkness, and sometimes even monsters that perpetuate the chaos! But with no knowable function, this “stuff” is nonexistent.

In his book, Genesis in Egypt: The Philosophy of Ancient Egyptian Creation Accounts, James B. Allen describes the difference between the Egyptian perspective of precreation nonexistence and creation in the following way:[7]

| Pre-creation/Nonexistence (no function) | Creation/Existence (functional) |

| Primeval flood, darkness | The Cosmos: Heaven and earth |

|

Infinite |

Bounded |

| Formless, chaotic | Shaped, ordered |

| Inert | Active, materially diverse |

Look for examples of this ancient Egyptian concept of nonexistence vs. existence as Genesis 1 moves from verses 1 and 2 to verse 31.

What about Creatio ex Nihilo?

Chances are all of us were taught the concept of creatio ex nihilo – the concept that nothing existed prior to God’s creation and that God made the world from nothing. Where does that concept come from? The concept, “creation out of nothing,” is not in the Old Testament. It is implied but never directly stated in the New Testament. We first see it named in the early Christian writer, Justin Martyr (c.100-165). But does Genesis 1 teach that God created out of nothing? Well, no and yes.

The complication is that creatio ex nihilo is based on a material understanding of creation rather than the ancient functional concept of creation. In the material perspective, Genesis 1 is not creation out of nothing. The earth, darkness and the deep already exist (Genesis 1:2) before God creates. But from a functional perspective, the earth, darkness and the deep are a “formless void” which, in the perspective of the ancient world does mean nonexistence.

Now let’s look for the priest’s passions and listen for his powerful message of hope as we work our way through Genesis 1.

Genesis 1: Reflections on the Text

God Creates Heaven and Earth as a Sanctuary, a Temple, a Holy, Good, Blessed Place

Genesis 1:1-2

In Genesis, the first three words in most English Bibles are, “In the beginning.” We hear those words and assume we are going to learn about the starting point of all creation. However, Othmar Keel and Silvia Schroer inform us that our assumption is incorrect because the English translation is incorrect. They write, “The meaning of (the Hebrew word) bere’sit is not ‘in the beginning’ but ‘at the time when.’”[8]

In Genesis 1, as in virtually every other creation story in the ANE, there was a primeval period—a period before creation. In Genesis 1:2 we read that “the earth” exists before creation. What the earth was like is described by the Hebrew words tohu wabohu translated, “formless void,” in the NRSV. Taken together, these Hebrew words mean uninhabitable, a wasteland with no discernable future. There is also “darkness” meaning timelessness. No past or future. And there is “the deep,” meaning great, chaotic waters.

As we saw in our introduction, this concept of precreation is common in ANE creation stories. But it is also an excellent description of what the exiles are experiencing. The priest begins his story of creation connecting directly with the life experience of the exiles. This is not simply a story about creation. It’s a story that begins with their experience. They are in a place that is also tohu wabohu and they know it! Then the story moves immediately to what God can and does do with tohu wabohu.

Jon Levenson is the Albert Al List Professor of Jewish Studies at Harvard Divinity School. He sees symbolic meaning in the words that describe primeval creation. He observes that in the Bible, “darkness” is a symbol of forces of evil allied against God. The “deep” is the source of the powerful monsters of chaos. Levenson explains, “Creation is a positive that stands in pronounced opposition to the harsh negative of chaos. The world is good; the chaos that it replaces or suppresses is evil…. The point of Bar Qappara’s [a rabbi in Israel from 180 to 220 CE] exegesis of Genesis 1:1–2 is that God did not create the good world out of nothing, but out of a malignant substratum.”[9]

Levenson concludes, “The point of creation is not the production of matter out of nothing, but rather the emergence of a stable community in a benevolent and life-sustaining order. The defeat by YHWH of the forces that have interrupted that order is intrinsically an act of creation.”[10]

The priest wants the exiles to know that God intervenes in the tohu wabohu. “The wind of God (ruah ‘elohim) sweeps over the face of the waters” (Genesis 1:2b). The wind is the life-creating force that pours out of God. In a recent sermon, Rev. Anne Turner linked this verse to John 20:20 where the risen Christ meets his fearful disciples who were hiding behind locked doors, breathes on them and says, “Receive the Holy Spirit.” This is what God did at Creation, at the exile, at the resurrection and in the times of disruption in our lives. God breathes God’s life-creating Spirit right into those moments.

Genesis 1:3

When we arrive at verse 3, we finally reach the first verbs of Genesis 1. A literal translation of the Hebrew is: “God said, ‘Let light be.’”

How does God make light? Notice, God speaks it into existence. Just as the Psalmist said,

By the word of the Lord the heavens were made,

And all their host by the breath of his mouth.

-Psalm 33:6

In Genesis 1, the priest author is affirming that God is the One who intervenes in chaos and darkness with his wind (Spirit) and Word to create, as we will see, order and blessing and goodness for all creation. This is what the priest wants the exiles to know as they live in the chaos and darkness of exile in Babylon. What God did at the beginning, God can and will do now. Their exile appears hopeless. What can slaves do against the greatest empire the world had seen? But there is hope. There is God’s presence each and every day.

God speaks. God says, (literal translation), “Let light be.” Light is not created. In another biblical creation story the Psalmist says,

You are clothed with honor and majesty,

wrapped in light as with a garment. -Psalm 104:1c-2a

At this point in Genesis 1, it is simply God’s presence—whether God’s wind, or God’s Word or God’s light—that intervenes. What is the priest teaching the exiles? The priest is stating that to live in the world God created is by definition to live the place where God’s life-creating Spirit breathes across our lives, where God’s living Word speaks life to us, where God’s light pushes back the darkness. So every day, exiles, past and present, need to prioritize looking for and building their lives on the wind, Word and light because it’s there. We can’t control it. But it’s there and the exiles need to affirm it in worship day after day, week after week. Again, the priest did not write Genesis 1 as a history lesson. He wrote it as good news for exiles. God has sent his Spirit and Word and light into this world for all time.

Introduction to Genesis 1:3-5

Notice in verse 3 that God saw that the light was “good.” The word, “good,” is a word we will hear throughout the creation story. When God is finished we read, God “saw everything he had made, and indeed, it was very good” (Gen 1:23). The Hebrew word translated “good” has many dimensions. It can mean well-being, wholeness, and holiness. Exiles need to look for it. And in our third session, we’ll see that when humans beings are made in the image of God, living out this goodness and creating this wellbeing, becomes each human’s life calling – in the exile, during COVID, throughout history.

In verse 4, we are introduced to a key verb in this story of creation. The verb “to separate” is used in verses 4, 6, 7, and 18. Yet it is not used in any other biblical story of creation. Why is it repeated in this story? Because down through the centuries, the priests taught and practiced careful separation in their ministry at the Temple in Jerusalem.

We see an example of the priests’ teaching in Leviticus 11. Priests did this separating work—separating the pure from the impure, the holy from the unholy—to maintain order and identity and well-being for the Hebrew people. Mark Smith explains the significance of placing this word in the story of God creating. In doing these acts of priestly separation, God is forming the cosmos, that is, all of creation as a Temple—a sacred space. Smith writes,

The implications for the picture of God are of singular importance… God not only creates; God is also the one who inaugurates separation into proper realms, and these realms are maintained in terms that echo the priestly regimen of the Temple. In this respect, God is presented not simply as the first builder. Genesis 1 further intimates that the universe is like a temple (or more specifically, like the Temple), with God presented as its priest of priests…. Within this worldview, creation in Genesis 1 is, in a sense, taking place in God’s divine sanctuary. Within this sanctuary, God generates the proper division of realms and animals, as the priests correspondingly do in the Temple.[11]

Creation is God’s sanctuary. The universe is a Temple. God’s light is always present. We will talk extensively about the significance of creation as God’s Temple in our next session when our topic will be Sabbath and Temple: Sacred Time and Sacred Space.

Genesis 1:3-31

We also see this aforementioned separating and ordering in the structure and symmetry that characterizes Genesis 1. In his book, The Seven Pillars of Creation: The Bible, Science, and the Ecology of Wonder, William P. Brown, Professor of Old Testament at Columbia Theological Seminary, describes this structure and symmetry which he calls, “The Genesis Code.” He also provides the following diagram. He writes:

Throughout Genesis 1 God goes about the work of “separating out” creation: light from darkness (1:4), waters above from waters below (vv. 6-7), and day from night (vv. 14, 18). As a result, discrete domains are established: light, water, sky, and land, each of which accommodates various entities, living and otherwise. In the course of the Genesis narration, both the domains and the members of these domains reveal an overarching symmetry. Call it the “Genesis Code.”

According to their thematic correspondences, the six days of creation line up to form two parallel columns. Their chronological ordering, in other words, gives rise to a thematic symmetry. Days 1-3 in the left column establish the cosmic domains, which are then filled or populated in the right column with various entities (Days 4-6). Read vertically, these two columns address the two abject conditions of lack described in Genesis 1:2, “void and vacuum.” The left column (Days 1-3) gives form to creation through the establishment of discrete domains, including light on Day 1, with Day 3 climactically depicting the growth of vegetation on the land. This concluding act vividly changes the earth’s primordial condition from its formless state of barrenness: the earth is no longer a “void” (tōhû) but a fructified land, providing the means for sustaining animal life. The right column, Days 4-6, fills these domains with their respective inhabitants, from celestial bodies that “rule” both day and night to human beings, who exercise “dominion.” The creative acts on Days 5 and 6 specifically change creation’s primordial condition from “vacuum” or emptiness (bōhû) to fullness. Genesis 1, in short, describes the systematic differentiation of the cosmos that allows for and sustains the plethora of life.[12]

Yes, creation is a wonder!

At this point, I would simply like to give two more examples of the priest author’s priorities.

Lights in the dome of the sky as signs

In verse 14, we read that the “lights in the dome of the sky” (the sun and the moon) are “signs” that define “seasons and days and years” (vs 14). What the author is saying is that even in exile, even in Babylon, even without the existence of the Temple, the sun and the moon are lights, “signs,” that call the Hebrew people to worship. Mark Smith explains, “The lights in Genesis 1:14 serve a specifically religious function, in marking the ‘appointed times,’ in other words, the festivals as known from the priestly calendars in Leviticus 23 and Numbers 28-29. The same word for festivals occurs at the head of the calendar in Leviticus 23:4. This usage also fits in with the Sabbath in Leviticus 23.”[13]

The author priest is reminding the exiles who are cut off from their homeland, cut off from their Temple which the Babylonians destroyed, that God has made creation as a Temple, a place of worship. Because God had made creation as a Temple for worship, the exiles are being called to worship the Creator in Babylon. Or today, on Zoom!

Blessing

My final example for today is the repetition of God’s blessing. (Note that we’ll focus on another example, the Sabbath, in our next session.) Blessing is what priests do. Why do priests bless? Because blessing is what God has called them to do. In Number 24:22-25, the Lord instructs Moses to teach the priests to bless the people:

22The Lord spoke to Moses, saying: 23Speak to Aaron and his sons, saying, Thus you shall bless the Israelites: You shall say to them, 24The Lord bless you and keep you; 25the Lord make his face to shine upon you, and be gracious to you; 26the Lord lift up his countenance upon you, and give you peace.

It’s not surprising that in the priestly story of creation, the God of wind, Word and light is the one who blesses. God blesses all the creatures in the sea, sky and land (1:22). God blesses humankind (1:28). And God blesses the Sabbath (2:3).

Why would blessing have been important to the exiles? Why is blessing important to us?

Conclusion

Genesis 1 is an exquisitely beautiful celebration of God’s love for and life-giving presence in creation. The climax (that we will focus on in our next meeting) is the Sabbath which is a call to worship and rest. The priest author knows the trauma of his people. He has experienced that trauma firsthand. As we’ll clearly see in Genesis 3 to 11, he knows how fragile creation is – how vulnerable it is to human evil.

So what is the priest teaching the exiles? Clearly, he is not teaching them science. This is not his entry into the evolution debate. Nor is he making a statement against grieving. In the Book of Lamentations, the Psalms and throughout the sixth century prophets, there are a multitude of texts that eloquently express multiple dimensions of grief. No, the priest is giving the exiles a map. He is saying, the Creator God is all around you. He is invested in creation – and is present in creation as Wind and Word and Light. God has and will transform this formless void into life that is good and blessed. Look for him, listen for him, worship him, follow him. He made this world as a sanctuary, a Temple, a holy place.

There are multiple signs in the text of Genesis 1 that strongly indicate the author was a priest. Why was a priest writing a creation story for these struggling people? As we just saw, Israel already had stories about the process of creation. Why one more? Why this one? Did the priest think they needed a lesson in ancient history? Did he write Genesis 1 as an entry for the science and faith debates of the 21st century?

No, the priest wrote or edited all of this content as a map for exiles. He wrote it for the people he loved and cared for every day. He wrote it for his people, exiled in Babylon, and suffering great trauma. It is a story about worship. It is a story about faithfulness—about love for God, neighbor and creation. It is a story declaring that because God, the loving Creator of this good and blessed world, is present with them in Babylon, they will have, even in exile, a blessed present and a blessed future. In writing Genesis 1 and organizing and editing chapters 2-11, the priest crafted a profound story of hope.

At the end of our session today, we’ll ask the question: What does Genesis 1, this story of creation, this love story, say to us today in our time of exile? What is it teaching us about how to live in this time when we are exiled from so much of what we love?

Reflecting on Spiritual Disciplines

I’m sure the experience of living in this time of pandemic is different for each of us. What is it like for you? For me it’s a combination of grief and disorientation. Or, to use other words, I experience loss and uncertainty. At times it’s like my life is set adrift. I need spiritual disciplines to ground me. They give my life a firm foundation on God’s presence with me and love for me, the people he created and the world he created.

Spiritual disciplines are practices that help us put what we believe into how we live. As I reflect on what we learn about faith from Genesis 1, two disciplines that come immediately to mind are:

- Worship

- Centering Prayer (see the addendum)

What comes to your mind? Let’s talk together about what actions, what spiritual disciplines we could engage in to integrate the meaning of Genesis 1 into our relationship with God and with others.

Rev. Dr. David Smith

Our Next Meetings

May 27, 28: Our Second of 6 Sessions

Genesis 2

Sabbath and Temple: Sacred Time and Sacred Space

June 10, 11: Our Third of 6 Sessions

Genesis 1 and 2

In the Image of God—What it Means to be Human

June 24, 25: Our Fourth of 6 Sessions

Genesis 3, 4 and 6

How did God’s Good Creation Tank?!

July 8, 9: Our Fifth of 6 Sessions

Genesis 11, 12 and 15

How Empires Work; How God Works

The Tower of Babel and Abraham

July 22, 23: Our Final Session

Sacred Space, Sacred Time Redux

Garden of Eden, Tabernacle, Temple, Isaiah, Ezekiel, Gospel of John, Jesus, Church, New Creation and Today

Addendum

Centering Prayer—Allowing God’s Presence to Form Me

We learn this approach to prayer from the Psalmist who said, “I have calmed and quieted my soul like a weaned child with its mother” (Psalm 131:2). The Psalmist is calling us to a form of prayer that is like the experience of a child who rests securely in a mother’s arms. Centering Prayer is resting in God’s presence. It is centering my heart (thinking, desires, motivation, emotions) in God.

How do we do Centering Prayer?

We knock, enter, engage with God, and then just sit in God’s presence.

Knock

Intentionally turn to God:

- God, I’ve been engaged in all this activity. Now I want to set it all down and turn to you.

- I humbly ask, “God, may I enter into your presence?

Enter

Choose a focus that centers my thoughts on God. It could be:

- A characteristic of God—God as Creator, or Christ healing the blind man.

- Or the character of God—the Father welcoming the prodigal son, God as sovereign over all, alpha and omega.

- Or a verse from God’s Word that reveals who God is.

Engage with God

Use that focus to reflect on and talk with God.

- God, thank you that you are. . .

- God, I see that you. . .

- I am so grateful that. . .

Sit in God’s Presence

Just be in God’s presence—1 min to 10 min. Just be there resting in the community (God the Father, Son and Spirit) of God’s sovereign love for you.

When it’s time to leave, thank God for the privilege and gift of being in God’s presence. God is the Father, Son and Spirit. You have been in THE community of love and joy.

Close by slowly praying the Lord’s Prayer.

Endnotes

[1] https://www.pinterest.co.uk/pin/484981453618456298/

[2] Ronald Hendel, The Book of Genesis: A Biography, Princeton University Press, 2013, 33.

[3] Mark S. Smith, The Priestly Vision of Genesis 1, Minneapolis, MN: Fortress Press, 2010, 43.

[4] Mark S. Smith, The Priestly Vision of Genesis 1, Minneapolis, MN: Fortress Press, 2010, 121.

[5] John H. Walton, Genesis 1 as Ancient Cosmology, Winona Lake, IN: Eisenbrauns, 2011.

[6] Quoted in Walton, ibid., 25.

[7] Quoted in Walton, ibid., 26.

[8] Othmar Keel & Silvia Schroer, Creation: Biblical Theologies in the Context of the Ancient Near East, Eisenbrauns, 2015, 140.

[9] Jon D. Levenson, Creation and the Persistence of Evil, Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 1994, xx-xxi.

[10] Levenson, ibid., 12.

[11] Mark S. Smith, ibid., 92-93.

[12] William P. Brown, The Seven Pillars of Creation: The Bible, Science, and the Ecology of Wonder, Oxford University Press, 2010, 37-38.

[13] Smith, ibid., 98.

Leave a Reply