Meeting 3 — Genesis 1 and 2

In the Image of God—What it Means to be Human

A Map for Exiles

We have seen God’s creating work as described in the seven days in Genesis 1 and the Garden of Eden in Genesis 2. Now we turn our attention to one part of God’s creation, namely, humanity. As the Psalmist reflects on the creation story, he marvels at the blessings God has given humanity.

3When I look at your heavens, the work of your fingers, the moon and the stars that you have established;

4what are human beings that you are mindful of them, mortals that you care for them?

5Yet you have made them a little lower than God, and crowned them with glory and honor. (Psalm 8:3-5).

The Psalmist goes on to say:

6You have given them dominion over the works of your hands; you have put all things under their feet,

7all sheep and oxen, and also the beasts of the field,

8the birds of the air, and the fish of the sea, whatever passes along the paths of the seas. (Psalm 8:6-8).

Here the Psalmist states the dominion God has given humanity. God has “put all things under their feet.” In Genesis 1, the fact that God has given this dominion to humanity results from God creating humanity in God’s image as we see in the following passage from Genesis 1:26-28:

26Then God said, “Let us make humankind in our image, according to our likeness; and let them have dominion over the fish of the sea, and over the birds of the air, and over the cattle, and over all the wild animals of the earth, and over every creeping thing that creeps upon the earth.” 27So God created humankind in his image, in the image of God he created them; male and female he created them. 28God blessed them, and God said to them, “Be fruitful and multiply, and fill the earth and subdue it; and have dominion over the fish of the sea and over the birds of the air and over every living thing that moves upon the earth.”

But there’s something strange going on here. To whom is the author of Genesis 1 speaking? He is speaking to Hebrew exiles, slaves in Babylon. In the 6th century BC, these are certainly some of the most powerless people on earth. And the Hebrew people living in Judah have always been a tiny nation. At this point the northern ten tribes no longer exist. And except for a brief period under the Maccabees who defeated the Seleucid Empire in 110 BD but then were defeated by the Romans in 63 BC, the Hebrew people will not have an independent nation until the 20th century AD! That doesn’t really look like dominion!

What is the author-priest talking about? What does it mean that God formed us in God’s image? What does it mean to be human?

Frame of Reference

Most people have heard of the biblical concept of the image God. But there’s a fair amount of confusion about what it actually means. My bias is that one of the reasons for the confusion is our frame of reference.

Over my years of ministry, my sense is that our primary frame of reference for understanding the image of God has been philosophical. People come at the discussion of the image of God by asking: What is the nature of humankind? There are many good reasons to wrestle with that question. But as we’ve seen, Genesis 1 was written by a priest to Hebrew exiles whose nation has been destroyed by the Babylonians whom the Hebrews are now serving as slaves.The exiles were not really wondering about philosophical questions. They were distraught, anxious and longing for a sign of hope and sense of direction.

The Babylonian Exile as Historical Context

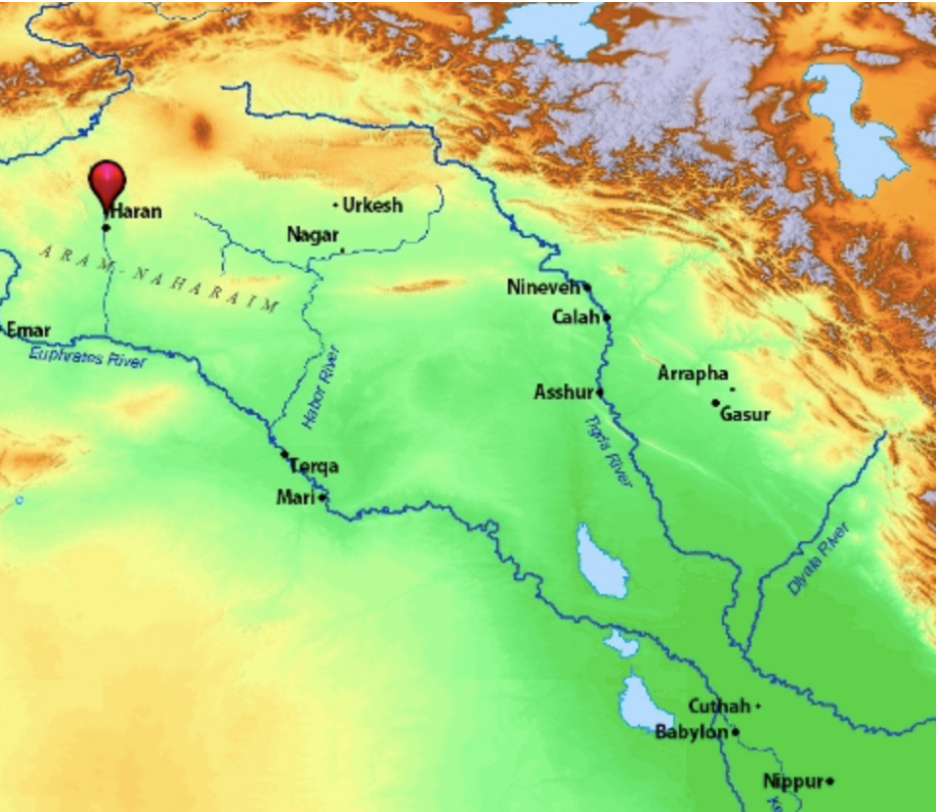

The Hebrew people are in exile in a land historically known as Mesopotamia. Mesopotamia is geographical region, not a nation. The Greek word, Mesopotamia, literally means, “the land between two rivers,” referring to the Tigris and Euphrates. This area is also known as the Fertile Crescent. The region of Mesopotamia extends from the Tigris and Euphrates Valley north to the Zagros Mountains and south to the Arabian Desert.

For these children of Abraham, being in “Mesopotamia” must have reminded them that they were in a shaky place. After all, God told Abraham to leave Mesopotamia and settle in the Promised Land. Apparently, there was something about the cultural environment of Mesopotamia that put Abraham’s fledgling faith in God at risk. We can’t tease out what that is. Scholars still are not sure in what time frame Abraham lived in Mesopotamia. In Genesis 12:1, a text we’ll look at in our final session, we see God’s words to Abram, “Now the Lord said to Abram, ‘Go from your country and your kindred and your father’s house to the land that I will show you.’”

But now, Abraham’s children are back in the region of Mesopotamia as exiles. God’s call to Abram implied that Mesopotamia was not a safe place for his nascent faith. And sure enough the Babylonians, the current rulers of Mesopotamia, have destroyed the primary identity markers of the Hebrew faith, namely, Solomon’s Temple and King David’s dynasty. On the surface, Babylon is a bright, shiny, impressive, powerful empire. It would be so easy for the Hebrew people to gradually assimilate into the impressive, overpowering Babylonian culture and ideology. If the Hebrews were assimilated into Babylonian society, Abraham’s faith and legacy would fade away. This is exactly what happened to the ten northern tribes of Israel a hundred years earlier. They were defeated by the Assyrians, taken into exile in Mesopotamia, and gradually through assimilation, disappeared, becoming what are often called the lost tribes of Israel.

For this reason, it’s absolutely essential that the exiles maintain their identity in Babylon. And, what is the author-priest saying to these exiles about being made in the image of God? What will empower them to maintain their identity while living as slaves in the powerful, mesmerizing empire of Babylon? When we remember that the priest is speaking to exiles, we see an astonishing identity affirming, countercultural declaration in these verses in Genesis 1:26-28:

26Then God said, “Let us make humankind in our image, according to our likeness; and let them have dominion over the fish of the sea, and over the birds of the air, and over the cattle, and over all the wild animals of the earth, and over every creeping thing that creeps upon the earth.” 27So God created humankind in his image, in the image of God he created them; male and female he created them. 28God blessed them, and God said to them, “Be fruitful and multiply, and fill the earth and subdue it; and have dominion over the fish of the sea and over the birds of the air and over every living thing that moves upon the earth.”

Let’s try to wrap our minds around the historical context in which the author-priest wrote these words. With that context as our frame of reference, we’ll unpack the priest’s specific words. We’ll also attempt to understand the vision the priest was creating for the exiles—a vision that spoke to their traumatic experience. As we listen, perhaps we can hear more clearly what it means we are made in the image of God. As we listen, let’s discern the map God’s Spirit is drawing for us in our exile.

By Creating Humanity on His Image, What is God Saying to the Exiles?

Conferring Dignity and Worth

Verse 26 begins with God saying, “Let us.” Let us? Who is us? In the six days of creation in Genesis 1, this is the first and only time God refers to “us.” Who is “us”?

In the Hebrew Bible, we see examples of God working with a council of heavenly beings. Here are some examples:

- 22Then the Lord God said, “See, the man has become like one of us, knowing good and evil; (Genesis 3:22).

- 8Then I heard the voice of the Lord saying, “Whom shall I send, and who will go for us?” (Isaiah 6:8)

- God tells Job about creation, 7when the morning stars sang together and all the heavenly beings shouted for joy? (Job 38:7)

What does it say about God that God chooses to collaborate with a heavenly council? In all of God’s glorious creation, only humanity is created by God’s council of heavenly beings. The priest’s point: Creating humankind in the image of God is so significant that it was done by God working with a heavenly council.

The message the exiles received from the Babylonians was: You are an insignificant, backwater, powerless slaves. The message the exiles receive from God is: You are incredibly significant, you have great worth and dignity. God and the entire heavenly council created you in the image God. This message of the dignity and worth of humankind is underscored throughout our reflection on the image of God.

Building Community Where All Are Welcome

The creation of humankind by God’s heavenly-being-community is emphasized with the repetitive plural pronouns in verse 27, “Let us make humankind in our image, according to our likeness.” God’s vision for humanity is that humanity would work and live as a community. God used a community to create that vision of humanity. To image God requires humanity to be engaged in community. Terence Fretheim describes God’s identity as a social being. He writes,

Israel understands that God is by nature a social being, functioning within a divine community that is rich and complex. God is not in heaven alone and, even more, is engaged in a relationship of mutuality within that realm. In other words, relationship is integral to the identity of God, prior to and independent of God’s relationship to the world. So when God decides to work communally in creation, God is being faithful to God’s own self.[2]

Fretheim takes God’s identity as working in community and applies it to the man God created in the Garden of Eden:

This divine council is also the most natural addressee of the words by God in Genesis 2:18: “It is not good that the man should be alone.” This likely context recognizes that aloneness is not characteristic of God, and hence the isolated human being would not truly be created in the divine image… Only the human being as social and relational to other human beings is truly correspondent to the sociality of God and what it means to be created in the image of God.[3]

The Babylonians are shredding the community of the Hebrew people. Babylonian violence has destroyed the exile’s historic, God given community markers. Not only that, many members of their community, family and friends, were murdered. Others, the poor, have been left in Judah to raise crops for Babylon. What God is saying to the exiles is that God is imaged in community. Therefore they need to intentionally rebuild their broken community. To be passive about rebuilding the community the Babylonians have shredded is to put their identity and future as the people of God at risk.

Today, we live in a culture that values individualism, self-assertion and self-fulfillment. People are naturally suspicious about church communities. More than that, the exile the coronavirus has placed us in means our church community is pulled apart. We cannot meet face to face in worship, coffee hour, children’s Sunday School, or adult groups. We cannot sing together in worship or receive the Eucharist. Like Babylon, the virus is shredding our community. To be passive about rebuilding our community in the age of coronavirus is as dangerous for our identity and future as the people of God as the exile was for the Hebrews.

Day by day, we each need to work at building community at St. Thomas. It reflects who God is, and it is intrinsic to what it means to be human.

Empowering the Powerless

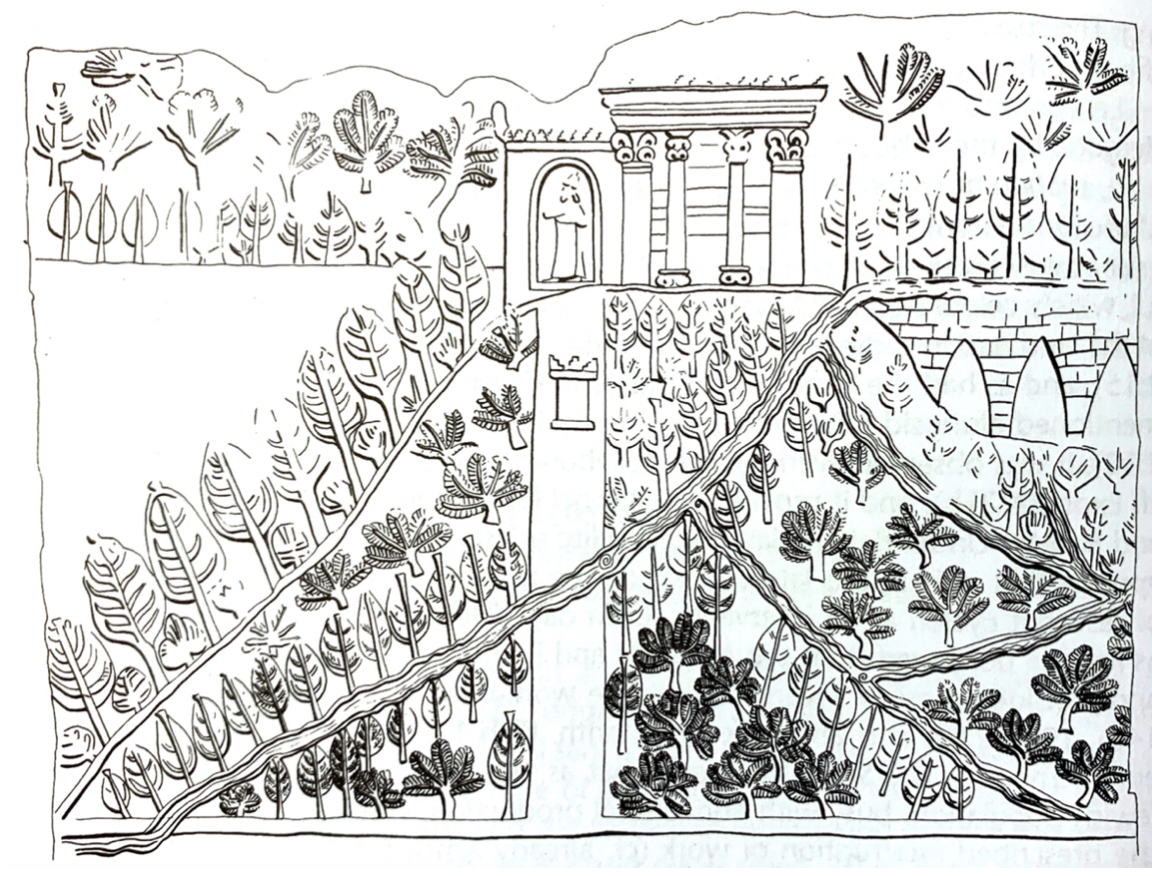

Now let’s turn our attention to what “image of god” meant in Ancient Near Eastern cultures. To help us, let’s take another look at a drawing we looked at in our last session. It is a drawing of a bas relief in the palace of Assyrian King Ashurbanipal. He lived less than 100 years before the Hebrews were exiles in Babylon. Here is the drawing of that relief from Othmar Keel and Silvia Schroer’s book entitled, Creation: Biblical Theologies in the Context of the Ancient Near East. The description from that book follows after the drawing.

Othmar Keel and Silvia Schroer describe this illustration:

The relief shows a temple site raised on a mountain. The immediate surroundings of the temple are indicated by trees and water. The water is brought in by means of an aqueduct. On the temple mountain it divides into several streams (cf. Gen 2:10-14). Beside or in the sanctuary, which is approached by a vis sacra, is a stela [stone column] with the image of a worshiping Assyrian king. [4]

This drawing illustrates the common understanding of image of god in the ANE world. In the majority of societies, the king is the image of god. The king’s responsibility is to rule on behalf of the god—asserting the god’s will over the people. The king also calls the people to worship god at the temple where the god is enthroned.

So in ANE societies, the king is the image of the god and people are essentially the servants of the god. Their responsibility is to provide whatever the gods need. Consequently, Richard Middleton sees Genesis 1:26-28 as a powerful countercultural statement—a vision for humanity that empowers the powerless. He writes,

The text highlights the radical distinction between oppressive Mesopotamian notions of human purpose as bond servants to the gods and a liberating alternative vision of humanity as the royal-priestly image of God.[5]

We remember our frame of reference. The author-priest of Genesis 1 is addressing people who are powerless. The Hebrew people are exiles, slaves, foreigners forced to serve the mighty empire of Babylon. Like Mary in the Magnificat (Luke 1:46-55), the author-priest is turning Babylonian cultural values upside down. His teaching that everyone, all humanity, is created in the image of God, not just kings. In this Babylonian setting, God is empowering the powerless.

Building a Community of God-Created-Uniqueness

But there’s more. The author priest goes on to state emphatically that women are also made in the image of God. As we read in Genesis 1:27, “So God created humankind in his image, in the image of God he created them; male and female he created them.” In a patriarchal world, this is an amazing, countercultural statement. The author priest also edited the creation of Eve in a way that underscores this countercultural statement.[6]

Before focusing on Eve’s creation. Let’s look at the creation of Adam as described in Genesis 2:7:

7Then the Lord God formed man from the dust of the ground, and breathed into his nostrils the breath of life; and the man became a living being.

The Hebrew word, ’adam, occurs a number of times in Genesis 1-5. The word means either humanity, a single male representative of humanity, or a particular individual. It’s impossible to know which definition is being used by just looking at the Hebrew word itself because it’s always the same. The only way to know which meaning to use is to look at the context in which it is used. In Genesis 1:27 we read:

27So God created humankind in his image, in the image of God he created them;

The Hebrew word translated “humankind” is ’adam. Here it’s translated “humankind” because it’s described by the plural pronoun, “them.” In some translations ’adam in this verse is translated, “man.” That’s not a helpful translation because in English, “man” can mean just males. And we know that understanding is incorrect because the next words in verse 27 are, “male and female he created them.”

In Genesis 2:7 we discover a different context. In this verse, ’adam occurs twice. Both times it occurs preceded by the definite article. In fact, in Genesis 2 ’adam occurs with the definite article 21 times. In Hebrew, the definite article is never attached to a personal names. With the definite article, the noun that follows is always an individual representing a group. So not, “man,” but, “the man” is a correct translation of every instance of ‘adam in Genesis 2. As John Walton writes, “When the definite article is being used, the referent is an individual serving as the human representative… the representational role is more important than the individual.”[7]

So when we read the story of God forming “the man” in Genesis 2:7, the emphasis is on the characteristics of all humanity (since Eve will be formed from “the man”). So, what do we learn about all humanity? In the Genesis 2 story of creation, humanity is made of “the dust of the ground” and God’s breath. The Hebrew word translated, “ground,” is, ’adamah, a word meaning “cultivatable land.” Notice the alliteration of the Hebrew. Humanity, ’adam, is made from ’adamah. To attempt that alliteration in English, we could say that we are earthlings created from the earth. “Dust” is a translation of a word that refers to “clumps of loose soil, not powdery dust.”[8]

There are two implications of this aspect of our creation. First, the literary connection between earthlings and the earth designates the interrelationship between humanity and the land. Humankind is dependent on the land for food (Genesis 1:29), and the land is dependent on the stewardship provided by humankind. God created interdependence between humankind and nonhuman creation. Second, to be created from clumps of loose soil means that humankind is mortal. We are not gods. We are made from the earth. As God says to Adam after he ate the forbidden fruit, “You are dust (same Hebrew word translated, “dust,” in Genesis 2:7), and to dust you shall return” (Genesis 3:19).

But we are also made from God’s breath. Without God’s breath we would be clumps of soil. But because of God’s Spirit, we have the gift of human life. In a deep and profound way, our lives are the gift of a loving God who wants to be in relationship with us. Our lives are also lives are dependent on the One who breathed us into existence.

We see this archetypal representation of all humanity in the creation of “the man” from dust. We also see the representation of all women in the creation of woman from “the man’s” rib. We read this story of the woman’s creation in Genesis 2:

21So the Lord God caused a deep sleep to fall upon the man, and he slept; then he took one of his ribs and closed up its place with flesh. 22And the rib that the Lord God had taken from the man he made into a woman and brought her to the man. 23Then the man said, “This at last is bone of my bones and flesh of my flesh; this one shall be called Woman, for out of Man this one was taken.” 24Therefore a man leaves his father and his mother and clings to his wife, and they become one flesh. 25And the man and his wife were both naked, and were not ashamed (Genesis 2:21-25).

What is the man’s “deep sleep”? John Walton does a detailed analysis of how the Hebrew words translated “deep sleep” are used throughout the Old Testament. He comes to the conclusion that deep sleep refers to “a visionary experience rather than a surgical procedure.”[9] What is this vision? It is seeing himself “being cut in half and the woman being built from the other half (Gen 2:21-22).[10] Walton notes that the word translated, “rib,” occurs 40 times in the Hebrew Bible but never as an anatomical term. He writes, “The word is only used architecturally in the tabernacle/temple passages (Exodus 25-38; 1 Kings 6-7; Ezekiel 41). It can refer to planks or beams in these passages, but more often it refers to one side or the other, typically when there are two sides (rings along two sides of the ark; rooms on two sides of the temple, the north or south side, etc.).”[11]

Walton notes that this vision “would give him an understanding of an important reality, which he expresses eloquently in Genesis 2:23.”[12] The vision means that ontologically, in other words, in her essence, the woman is the same as the man. The vision makes clear that the woman is not some kind of subspecies of “the man” or a second rate human. It is a relationship of equality because man and woman both have the same essence. As the man says, “This at last is bone of my bones and flesh of my flesh; this one shall be called Woman, for out of Man this one was taken.” The Hebrew word for Man (the archetype) is ’iš. Meyers notes that the Hebrew word ’iš occurs “more than 2,000 times in the Hebrew Bible, its primary sense is to note an individual who is representative of a group.[13] The word for Woman is ’iššah. The assonance of the two Hebrew words points to the equality between them.

We also see this equality in God’s description of the relationship between man and woman when he said, “It is not good that the man should be alone; I will make him a helper as his partner.” (Genesis 2:18). To understand the meaning of “helper as his partner,” we need to understand how these Hebrew words are used in other places In the Old Testament. The word, “helper,” cannot mean, “subordinate,” because it is also used to refer to God (Genesis 49:25). The word translated partner, kenegdo, means “corresponding to” or “on a par with.” Carol Meyers explains the meaning of kenegdo, “The two people will be neither superior nor subordinate to each other; the phrase connotes a nonhierarchical relationship… ‘partner’ suggests that the two were once part of each other. ‘Counterpart’ would be similarly apt in designating the second person as of the same essence as the first; the two complement each other.”[14]

As we continue to unpack the meaning of “the man” and woman as archetypes of all men and women, we note that God has made them both equal and different. The difference has a purpose. God states that purpose in Genesis 1:27b, 28a where we read, “male and female he created them. God blessed them, and God said to them, ‘Be fruitful and multiply, and fill the earth.’” Again, speaking archetypally, Genesis 2:24 states what will need to happen for God’s vision to be accomplished, “Therefore a man leaves his father and his mother and clings to his wife, and they become one flesh.” In our next session, we will study about Adam and Eve realizing they’re naked and feel ashamed. Then we’ll unpack the meaning of Genesis 1:25, “And the man and his wife were both naked, and were not ashamed.”

So let’s pause and summarize what we have learned here about Gpd’s creation of humankind as male and female. These are profound truths. Ontologically, men and women are equal—made of the same essence. The man is made of soil and God’s breath. The woman is made from man. Same essence. They are counterparts—partners in doing the work of imaging God. And their God created difference enables them to engage in God’s mission of filling the earth. God is imaged in the uniting of God created diversity.

Let’s remember this theme when we arrive at Genesis 11, the Tower of Babel story, and read in verse 9, “Therefore it was called Babel, because there the Lord confused the language of all the earth; and from there the Lord scattered them abroad over the face of all the earth.” Here again is God created diversity—diversity that is essential to God vision for his creation. On Pentecost, we see God unite that diversity in the birth of the church. Diversity is not erased. It is united by God’s Spirit. God is imaged in the unity of God created diversity.

Embracing a New Definition of Having Dominion and Subduing

To live as the image of God is to exercise dominion over and subdue (Gen 1:26, 28). What does this calling say about God? And what does having dominion and subduing look like?

God’s call for humanity to exercise power in creation teaches us that God shares power. God steps back, so to speak, to give humanity room to do what God created humans to do. God entrusts the well-being and future of his beautifully crafted creation to humanity. But for humanity to be what God created them to be, humanity needs to be engaged in having dominion and subduing.

So what do the words “have dominion” and “subdue” mean? Warning!! Those of you who were in the Revelation class have heard this many times. If we take the English words of the Bible and simply define them according to our own frame of reference, chances are that we will misinterpret what the Bible is saying!

When we hear these words in English, we immediately envision power asserting itself over human and nonhuman creation. But wait. Isn’t that exactly what the exiles have experienced from Babylon? Babylon has dominated and subdued them as a people. Is the priest teaching the exiles that God expects them to be better at being Babylon than Babylon is? Babylon has reduced the Hebrews to the state of tohu wabohu. Is the author-priest teaching the exiles to image God by dominating and subduing and creating tohu wabohu even more forcefully than the Babylonians have done to them?

We must allow the Bible to tell us what these words, “dominion,” and, “subdue,” mean. I suggest three ways to do that. First, we need to analyze how God models dominating and subduing in Genesis 1. Second, we need to assess how Jesus Christ, the Son of God, dominates and subdues. Third, we need to see biblical examples of dominating and subduing in ways that God commends. So…

How does God dominate and subdue?

What have we seen God do in Genesis 1? God intervenes in tohu wabohu and creates order, blessing, beauty, and what is very good. God creates shalom, well-being, for all. How does God do that? Many ANE creation stories, for example the Babylonian Enuma Elish, show the gods creating by violently overthrowing and killing the gods of chaos. But in Genesis 1, God has dominion over and subdues tohu wabohu not through the power of violence but the power of Wind, Word, and Light.

How does Christ dominate and subdue?

We could certainly place all four gospels here to illustrate. There are countless examples. Think of parables like the way the Good Samaritan intervenes in the tohu wabohu of the man beaten and robbed on the road to Jericho. Think of the way the father intervenes in the tohu wabohu of his lost Prodigal Son and the angry elder brother. Think of stories like the Samaritan woman at the well. Good Jewish men would have avoided her. But Jesus intervenes in her tohu wabohu of five husbands and living with a sixth man. Jesus goes to her, accepts her, talks with her, listens to her, lovingly speaks truth and empowers her.

Think of Jesus’ teaching. Jesus teaches his disciples about a way in which God holds all people accountable in the story of the sheep and the goats. The sheep are the ones whom God affirms in eternity. God affirms them for the way they dominated and subdued by intervening in tohu wabohu. Jesus tells this story:

34Then the king will say to those at his right hand, ‘Come, you that are blessed by my Father, inherit the kingdom prepared for you from the foundation of the world; 35for I was hungry and you gave me food, I was thirsty and you gave me something to drink, I was a stranger and you welcomed me, 36I was naked and you gave me clothing, I was sick and you took care of me, I was in prison and you visited me.’ 37Then the righteous will answer him, ‘Lord, when was it that we saw you hungry and gave you food, or thirsty and gave you something to drink? 38And when was it that we saw you a stranger and welcomed you, or naked and gave you clothing? 39And when was it that we saw you sick or in prison and visited you?’ 40And the king will answer them, ‘Truly I tell you, just as you did it to one of the least of these who are members of my family, you did it to me.’ (Matthew 25:34-40)

When the disciples are arguing about who will rule with Jesus, Jesus teaches them his meaning of dominating and subduing. He says, “You know that among the Gentiles those whom they recognize as their rulers lord it over them, and their great ones are tyrants over them. 43But it is not so among you; but whoever wishes to become great among you must be your servant, 44and whoever wishes to be first among you must be slave of all. 45For the Son of Man came not to be served but to serve, and to give his life a ransom for many.” (Mark 10:42-45)

Examples of dominating and subduing in the Old Testament

We begin in the Garden of Eden. God said that it is not good that the man should be alone and so is looking for a partner (as we discussed above). So God forms “every animal of the field and every bird of the air” (Gen 2:19), brings them to the man “to see what he would call them.” The tohu wabohu here is the absence of needed community. So what does dominating and subduing look like? Does the man assert his will over the animals? No, the man must discern the nature of each animal. It is a process of observing, in a sense, listening, and honoring the God created nature of each. Then the man gives the animal a name that describes the animal’s distinctive nature. Dominating and subduing is being committed to learning, honoring and naming the nature of the animals God created.

In the prophets there are many examples of dominating and subduing as it is described by God in contrast to the way it is practiced by empires. Here is an example from Isaiah 42 which was written during the time of the exile. It describes one who is the servant of the Lord. God then describes himself as creator and states the mission he has given his people. Notice how dominating and subduing is described:

Here is my servant, whom I uphold, my chosen, in whom my soul delights; I have put my spirit upon him; he will bring forth justice to the nations. 2He will not cry or lift up his voice, or make it heard in the street; 3a bruised reed he will not break, and a dimly burning wick he will not quench; he will faithfully bring forth justice. 4He will not grow faint or be crushed until he has established justice in the earth; and the coastlands wait for his teaching.

5Thus says God, the Lord, who created the heavens and stretched them out, who spread out the earth and what comes from it, who gives breath to the people upon it and spirit to those who walk in it: 6I am the Lord, I have called you in righteousness, I have taken you by the hand and kept you; I have given you as a covenant to the people, a light to the nations, 7to open the eyes that are blind, to bring out the prisoners from the dungeon, from the prison those who sit in darkness. (Isaiah 42:1-7)

My final example is from Psalm 72 where a king’s responsibility for dominating and subduing is laid out:

1Give the king your justice, O God, and your righteousness to a king’s son.

2May he judge your people with righteousness, and your poor with justice.

12For he delivers the needy when they call, the poor and those who have no helper.

13He has pity on the weak and the needy, and saves the lives of the needy.

14From oppression and violence he redeems their life; and precious is their blood in his sight. (Psalm 72:1,2,12-14)

To conclude this section on what it means to have dominion over and subdue, I turn to William Brown. He writes, “Humanity’s ‘regime’ over the world in Genesis 1 is constructive, even salutary, consonant with God’s life-sustaining creation. The language of ruling and subduing is in the hands of the Priestly narrator transformed. Humanity’s “dominion” is unlike any other kind of dominion, certainly far from modernity’s well-known triumphalistic anthropology.”[15]

Serving as Priests—To Till and To Keep

In Genesis 2, we find another clue of what it means to live as the image of God. In Genesis 2:15 we read,

15The Lord God took the man and put him in the garden of Eden to till it and keep it.

We read these words and immediately assume that God put the man in the garden to be the gardener. Gardeners till and keep gardens. That’s our frame of reference. However, when we switch our frame of reference to biblical context we discover something else entirely. The Hebrew verbs translated “till” and “keep” are ‘bd and šmr. John Walton writes that the verb šmr is used for the duties of priests. He writes, “The verb šmr is used in the contexts of the Levitical responsibility of guarding sacred space… Caring for sacred space should be seen as much more than landscaping or even priestly duties. Maintaining order made one a participant with God in the ongoing task of sustaining the equilibrium God had established in the cosmos.”[16]

We find an example of these two verbs, ‘bd and šmr, used in the way Walton describes in Numbers 3:5-8.

5Then the Lord spoke to Moses, saying: 6Bring the tribe of Levi near, and set them before Aaron the priest, so that they may assist him. 7They shall perform duties (šmr) for him and for the whole congregation in front of the tent of meeting, doing service (‘bd) at the tabernacle; 8they shall be in charge (šmr) of all the furnishings of the tent of meeting, and attend to the duties (šmr) for the Israelites as they do service (‘bd) at the tabernacle.

Notice that the Hebrew verb translated “till” in Genesis 2:15 is translated “perform duties” and “do service” in Numbers 2:7,8. The verb translated “keep” in Genesis 2:15 is translated “duties” and “be in charge” in Numbers 2:7,8.

So what do these priestly verbs mean for the man as representative of all humanity? They mean that God is calling humanity to serve as priests in the sacred space of God’s Temple and God’s Temple is creation.

Humanity’s responsibility is to be priests in the sacred space that God created and where God dwells. We are priests who serve and honor God by protecting sacred space, keeping out all that would violate it. And priests, like the creator God, work creatively to help creation flourish in the order, goodness and blessing God intends.

We see this priestly vision for humanity throughout the Bible. When God meets with the Hebrews he freed from slavery in Egypt, God invites them to be a kingdom of priests (Exodus 19:6). After Christ’s death, resurrection and ascension, Peter picks up that same description and applies it to the church as the priesthood of all believers (1 Peter 2:5,9). And at the beginning of Revelation, John writes: To him who loves us and freed us from our sins by his blood, 6and made us to be a kingdom, priests serving his God and Father, to him be glory and dominion forever and ever. Amen. (Revelation 1:5b,6)

Being Fruitful, Multiplying, Filling the Earth

God creates. Creating is at the heart of who God is. So the image God involves being creative too. And God bestows the freedom and even commands the power to create. After God creates the living creatures in the sea and sky we read: 22God blessed them, saying, “Be fruitful and multiply and fill the waters in the seas, and let birds multiply on the earth.” (Genesis 1:22)

After creating humanity, we read: 28God blessed them, and God said to them, “Be fruitful and multiply, and fill the earth and subdue it; and have dominion over the fish of the sea and over the birds of the air and over every living thing that moves upon the earth.” (Genesis 1:28)

God blesses the animals with the power to procreate. Then God blesses humanity with the power to procreate but adds the responsibility to subdue and have dominion. And that addition, using the definitions of subduing and having dominion we described above, expands God’s call for humanity to be creative in every aspect of life. It is an invitation to every person to discern God given abilities and skills and use their uniqueness to bless God’s creation. As Terence Fretheim writes,

This divine move constitutes a sharing of power. God gives the human being certain tasks and responsibilities and, necessarily, the power with which to do them. From the beginning, God chooses not to be the only one who has creative power and the capacity, indeed the obligation, to exercise it. Given the imaging of God as one who creates, these words of commission should be interpreted fundamentally in terms of creative and communal word and deed. Human beings are invited to play an important role in the becoming of their world, indeed, bringing into being that which is genuinely new… Human beings are given a crucial role in enabling the creation to become what God intends[17]

Application

I believe that the theme we see running through these examples, and indeed throughout the entire Bible is that to be created in the image of God means we are to live in such a way that our words and actions reflect who God is. Reflecting on the meaning of being made in the image of God, Mark Smith writes, “Humanity is not only the representation of God on earth; the human person is the living representation pointing to a living and real God.”[18]

What an astonishing statement to exiles! And what a contrast to the tendencies of our society. Western culture certainly tends toward being individualistic, self-centered and self-fulfilling. We are inclined toward developing methodologies and techniques we can use to assert our power and get what we want. In other words, Western culture is not all that different from the Babylonian Empire.

How do we as humans emulate, image this God? Not by acting like Babylonian emperors. What do we do? We live the kind of life worthy of our humanity as people God made in his image. We follow God’s example. We do it by actually seeing situations of tohu wabohu, situations of chaos and void around us and with humility, stepping in, taking initiative. As we have seen, we engage in:

- Conferring Dignity and Worth

- Empowering the Powerless

- Building a Community of God-Created-Uniqueness

- Embracing a New Definition of Having Dominion and Subduing

- Serving as Priests—To Till and To Keep

- Being Fruitful, Multiplying, Filling the Earth

June 24, 25: Our Fourth of 6 Sessions

Genesis 3, 4 and 6

How did God’s Good Creation Tank?!

July 8, 9: Our Fifth of 6 Sessions

Genesis 11, 12 and 15

How Empires Work; How God Works

The Tower of Babel and Abraham

July 22, 23: Our Final Session

Sacred Space, Sacred Time Redux

Garden of Eden, Tabernacle, Temple, Isaiah, Ezekiel, Gospel of John, Jesus, Church, New Creation and Today

Rev. Dr. David Smith

[1] https://leonmauldin.blog/2010/05/07/haran-of-aram-naharaim-mesopotamia/

[2] Terence E. Fretheim, Creation Untamed, Grand Rapids: MI, Baker Academic, 2010, 28.

[3] Ibid., 28-29.

[4] Illustration and description, Othmar Keel & Silvia Schroer, Creation: Biblical Theologies in the Context of the Ancient Near East, Eisenbrauns, 2015, 66.

[5] J. Richard Middleton, The Liberating Image: The Imago Dei in Genesis 1 Grand Rapids, MI: Brazos Press, 2005, 210.

[6] One way scholars know that the author-priest edited the rest of Genesis is the use of the priestly term, toledot (translated, “generations,”), in Genesis 2:4a to link Genesis 1 and 2 together. He uses toledot 10 more times in the book of Genesis to link sections together.

[7] John H. Walton, The Lost World of Adam and Eve Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 2015, 61.

[8] Carol Meyers, Rediscovering Eve: Ancient Israelite Women in Context New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2013, 71.

[9] Walton, ibid., 79.

[10] Ibid., 79-80.

[11] Ibid., 78.

[12] Ibid., 80.

[13] Meyer, ibid., 76.

[14] Meyer, ibid., 73-74.

[15] William P. Brown, The Seven Pillars of Creation: The Bible, Science, and the Ecology of Wonder New York: NY, Oxford University Press, 2010, 47.

[16] Walton, ibid., 106-107.

[17] Ibid., 31 and 68.

[18] Smith, ibid., 101.